About Termites

Introduction

Formosan termites are not native to the United States. The Formosan subterranean termite (FST), Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki, was introduced into the United States via infested wooden cargo crates and pallets returning from eastern Asia after World War II. It was first collected in South Carolina in 1957, but was not positively identified until it was collected in Houston, Texas in 1966. The southeast US has a warm climate that has allowed this species to flourish. Furthermore, there were approximately two decades from its introduction to its identification, which allowed this cryptic species to expand its non-native range uninterrupted.

FST continues to spread by human transport of infested materials such as railroad crossties used in the construction of retaining walls and other landscape features (Figure 1). FST infestations have been found in at least 12 states. See more information on the Formosan subterranean termite’s distribution in the US.

Learn to Recognize the Formosan Subterranean Termite

It is important that pest management professionals are able to differentiate between the Formosan subterranean termite and the native subterranean termites (e.g., Reticulitermes species). In short, Formosan subterranean termites can be differentiated from native subterranean termites by the following three criteria:

Differences in Swarmers/Alates

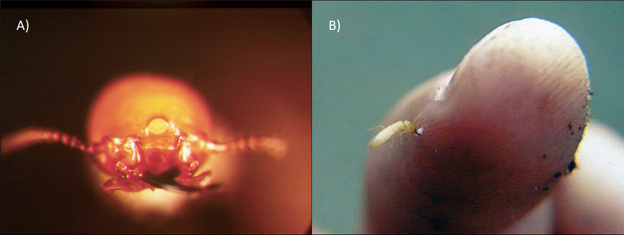

Formosan termite swarmers (technically known as alates) are larger than native subterranean termite swarmers, measuring one-half of an inch from tip of head to tip of wings, and the body is caramel- to brownish-yellow in color (native termite swarmers are usually black and three-eighths of an inch long from tip of head to tip of wings) (Figure 2). It is important to note that size and color of insects can vary within species, and that there are other species of termite that can potentially look similar in appearance and/or swarm during the same time of year. If you have questions about termite identification, please contact a collaborator of the North American Termite Survey (NATS) or your state extension service.

Formosan subterranean termite alate wings are covered with hairs and can be seen using magnification. Wings of native subterranean termite alates do not have hairs. Formosan subterranean termite swarmers are caramel to brownish-yellow colored, while native subterranean termite swarmers are black (not shown).

Difference in Swarm Time and Season

Formosan subterranean termites

- swarm at night

- swarm in late May and/or early June, depending on the state

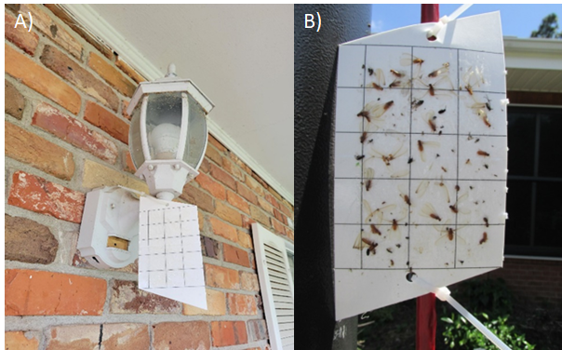

- swarmers are attracted to light (Figure 3)

Depending on the state, native subterranean termites begin swarming in February/March, swarm during the day, and do not swarm around lights at night. To find evidence of a previous Formosan termite swarm, look for dead, dried swarmers or their wings in window sills, in spider webs (indoors and outdoors), and inside porch light covers. Employees who answer the phone in response to swarmer calls should be made aware that Formosan subterranean termites swarm at night during May and June. In the rare case that a caller indicates a “night swarm”, receptionists are encouraged to pass this information on to an owner and/or manager.

Differences in Soldiers

Formosan subterranean termite soldiers make up as much as 10–20% of the termites in a colony, compared with just 1–3% in a native subterranean termite colony. Generally, if a colony is breached and a large number of soldiers are immediately evident and aggressive, the termites are likely Formosan (Figure 4). Formosan subterranean termite soldiers also exude a white, glue-like secretion from the top of their head when harassed; native subterranean termite soldiers do not exude this material (Figure 5). If challenged, Formosan termite soldiers may also try to bite. However, their bite is not painful or dangerous in any way.

Formosan alate swarm season by state

| State | FST Swarm Season |

|---|---|

| Alabama | Late May to June |

| Arkansas | N/A |

| California | Late May to early August |

| Florida | Late March to July |

| Georgia | Late May to early June |

| Kentucky | N/A |

| Louisiana | April to mid-June |

| Mississippi | May to June |

| North Carolina | April to June |

| South Carolina | Mid-May to July |

| Tennessee | Early May to end of June |

| Texas | Late May to early June |

Termites vs. Ants: Telling Swarmers Apart

Termites are not the only insects who have swarming behaviors to ensure reproductive success. Their age-old nemesis, the ant, also swarms seasonally and can be commonly mistaken for termite swarmers. Don’t panic, and instead catch one of the flying pests and take a look for these three key differences:

Antenna Shape

One of the most distinct differences between ant and termite swarmers is the shape of their antenna. Ants have what we scientists refer to as “geniculate” antennae, or antennae that bend like an elbow. Termites on the other hand have “moniliform” antennae, or antennae that are straight and beaded (Figure 6).

Wing Length

As you already know, these insects currently possess wings, and they actually have four of them, or two pairs. In ants, these two pairs of wings are different lengths, with the front wings (forewings) being much longer than the rear wings (hindwings). In termites both their fore- and hindwings are the same length and size (Figure 6).

Waist Width

Continuing down the body of the insect we arrive at the waist – the connection point between the insect thorax (where the wings and legs are) and the abdomen (colloquially called the “butt”). In ants the waist is pinched, at times so tightly that it is hard to see without magnification. This gives ants the appearance of having really large and bulbous abdomens. However, with termites, the waist is broad, really almost the entire length of their abdomen will be roughly the same width (Figure 6).

Termite Biology & Lifecycle

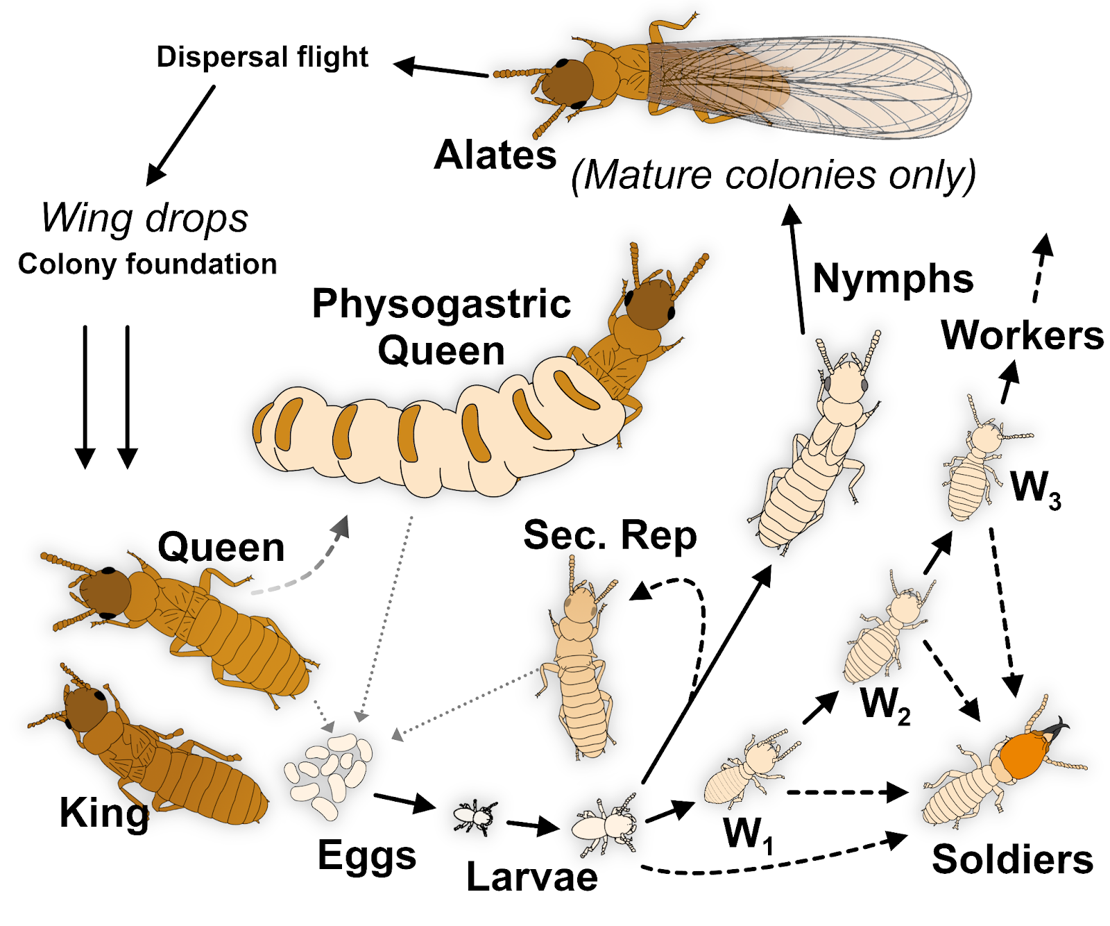

Termites are eusocial insects in the same order as cockroaches (Order: Blattodea). They are known for their complex social structures and are great decomposers. While all termites generally progress through three main stages—egg, nymph, and adult—the specifics of caste differentiation, colony development, and reproductive behaviors vary significantly among different types of termites.

Subterranean termites have large colonies and a highly organized caste system, and their lifecycle emphasizes continuous expansion and adaptability. Their reliance on soil moisture necessitates a life cycle that includes significant interaction with the subterranean environment. Their colonies consist of distinct castes: workers, soldiers, and reproductive kings and queens. The life cycle begins when a mature queen lays up to 2,000 eggs daily, which hatch into nymphs. Nymphs undergo multiple molts to develop into one of three castes, determined by colony needs and environmental factors. The most numerous caste workers are responsible for foraging, nest maintenance, caring for the young and queen. Soldiers, equipped with strong mandibles and defensive secretions, protect the colony from predators like ants. Reproductives, or alates, are winged termites that leave the colony during the swarming season, typically in late spring or early summer, to mate and establish new colonies. After the nuptial flight, they shed their wings and pair up to form a new king and queen. The newly formed pair begins laying eggs to develop a new colony, starting with a small worker population. Over time, the colony expands significantly, with mature colonies often exceeding several million individuals. Formosan termites also have secondary reproductive (neotenic development) that can arise within the colony to supplement egg production or replace the queen if necessary. This ability contributes to their resilience and rapid expansion.

Signs of the presence of Coptotermes formosanus

Mud tubes

Key signs include the presence of mud tubes, which the subterranean termites construct to travel between their underground nests and food sources. These tubes, made of soil, wood particles, and saliva, provide moisture and protection as they forage. Mud tubes created by Formosan termites are distinctive structures that can be identified by their composition, appearance, and location. These tubes are compact and have a slightly rough texture. They are often found running along foundations, walls, or other surfaces as termites travel between their underground nests and food sources. Termite mud tubes are typically about the width of a pencil and may branch into multiple paths, creating a network-like structure. In contrast, tunnels made by other insects, such as ants, are usually smoother and less uniform. Ant tunnels lack the soil-and-wood mixture characteristic of termite tubes and are often smaller in diameter. Mud-dauber wasps, another potential source of confusion, construct mud nests that are tubular or cell-like in shape but unrelated to wood damage and often located in sheltered areas like ceilings or eaves.

To determine if a termite mud tube is active or abandoned, several simple but effective methods can be employed. The most direct approach is to gently break a small section of the tube and observe the reaction. In an active mud tube, termites will often become visible within minutes, scurrying to repair the damaged section. If no termites are present, it could indicate that the tube is abandoned or temporarily inactive.

Swarming

Another indicator of the presence of termites is swarming behavior, particularly in late spring or early summer, when winged alates (reproductive termites) emerge to mate and establish new colonies. After swarming, discarded wings near window sills, doorways, or light sources often signal their presence.

Discarded wings and termite droppings

Termites shed their wings after finding a mate, so seeing wings on window sills or other surfaces signifies an infestation. The appearance of frass (termite droppings) near wooden structures can also indicate an infestation.

Signs of damage

Structural/tree/wood damage: Formosan termites can rapidly hollow out wood, leaving a thin outer shell intact. Termites can damage paint, sheetrock, and flooring. The damage could also appear as blistered or buckling wood and may cause doors, windows, or floors to warp. Carton nests, a spongy material made of chewed wood, soil, and feces, indicate an infestation. These nests are often found within walls or other voids and retain moisture to support satellite colonies.

Sometimes, clicking or rustling sounds from inside walls may be heard, caused by termites communicating or chewing through wood. Formosan termites can cause wood to crack, discolor, or become soft and spongy. They often nest in places with lots of wood and fiber, like crawl spaces. Termites eat wood from the inside, which can make floors and walls sound hollow.

Other subtle signs include unexplained blistering of paint, which occurs when termites burrow close to the surface, and accumulations of frass (termite droppings) near infested areas.

Formosans target wooden structures in contact with soil, such as foundation beams, posts, or joists, as these areas provide moisture and direct access to their underground nests. Cracks in foundations, gaps in mortar, and unsealed joints are common entry points, as Formosan termites can infiltrate through even the smallest openings (as narrow as 1/16 of an inch). Damp or water-damaged wood is particularly attractive, as it is softer and easier to chew. Plumbing leaks, clogged gutters, or poor drainage around the structure can create moisture conditions that draw termites to these areas. They also exploit foam insulation boards, which they use to tunnel through walls or reach higher levels of buildings. Once inside, termites can move vertically, attacking framing, subflooring, and roof timbers.

This article is based on the Identifying the Formosan Subterranean Termite, Fact Sheet, Daniel R. Suiter, Ph.D., Department of Entomology, Griffin, GA, and Brian T. Forschler, Ph.D., Department of Entomology, Athens, GA